Long-time identity expert and SGNL Advisor Ian Glazer from Weave Identity has written an insightful post about why we need to refactor our thinking about the principle of least privilege. At SGNL, we have long advocated that moving towards Zero Standing Privilege is the true goal.

For too long we have been stuck with "least privilege" being equal to the total entitlements required to perform a job over time. Unfortunately that time period trends towards employment lifetime (i.e. months and years) or, at best, the time between access reviews. In math terms, privilege ends up being the total area under a graph of entitlements over time.

This creates an enormous surface area for attack and exploitation as seen almost weekly with the impact of identity breaches and session hijacking. Instead, we should assume an identity breach has happened and take a zero standing privilege posture from the start. To achieve that, we need to redefine least privilege as the minimum "what is needed right now for the task at hand" and not "what might I need right now."

-Erik, CPO / co-founder @ SGNL

An admission: I have become a bit of an identity governance and administration (IGA) nihilist. This, for those of you who know my background, is a big admission. I grew up a user provisioning person in this industry. I wrote extensively about access certification. I studied role management.

And, in a lot of ways, I have come to believe that IGA has failed. It works great for birthright access assignment but role management and access certification have missed the mark. This is not for lack of heroic efforts on the part of earnest practitioners nor for lack of massive investment in products and tools.

When I was at Gartner, long ago, I wrote about the power and necessity of entitlement catalogs. You have to know what an entitlement does before you can review whether it is appropriate for someone to have or not… and you need to know what it does before you combine them into roles and dole them out. An entitlement catalog, in any form, is needed. And in my naivety I thought enterprises would dedicate the resources needed to build and, most critically, maintain entitlement catalogs. I was wrong. That did not, and in some regards cannot, happen. So why lead with this admission? Well, I was kicking around some ideas with my friend and client, Erik Gustavson of SGNL, and we unintentionally hit at a nagging doubt stemming from my blooming IGA nihilism…

Least privilege is a lie.

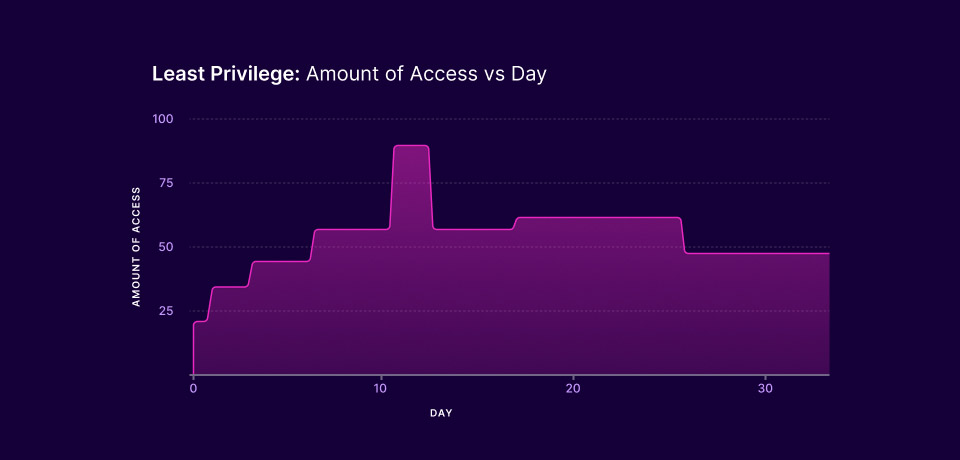

The principle of least privilege states that a person should have only the access rights they need to perform their job functions and nothing more. The acts of access certification and role management support this goal. Using least privilege, I would receive a set of birthright entitlements when I get hired, and over time, likely via access requests, I would get more access to enable me to do my job. So if we graph my access rights over time it would look something like this:

Least Privilege: Amount of Access per Day

On Day 0 the individual has no access rights. Birthright provisioning kicks in, followed by access requests, and the amount of access increases. (And yes I know how poor form it is to have a graph with no units of measure… hit me in the comments with your suggested label.) Over time, the person’s access increases and decreases but in that graph I cannot spot “least privilege,” can you?

We can think about the area under the line as the access rights, no matter how meager, that an adversary can use as they live off the land. That area, measured in access rights over time, is never zero in a least privilege world.

To be clear, I am not demonizing our collective efforts. Really great people have spent an enormous amount of time and effort to protect their organizations through the principle of least privilege. Auditors have conducted a gazillion audits to validate least privilege practices.

So the very reasonable response to all this is “Well, anyone can tear down a wall, but building a house is a lot harder.” I posit that if we stop thinking of least privilege as a destination, as the goal of our efforts, we’ll be better off. If we acknowledge that least privilege as a destination is a lie, it frees us to try something else. Instead, let’s think about least privilege as a verb – the act of reducing standing access. If least privilege isn’t a destination, then what is?

Zero standing privilege.

The gang at SGNL use the term zero standing privilege, and I am really starting to love this idea. The idea being that the goal we seek is that user accounts should have no standing access rights – meaning that absent anything, the user account can do nothing except log in.

Well logging in is fine and all, but not that useful. ZSP implies that access rights are granted at, ideally, the moment of use. Or, more realistically, when a session or access token is created.

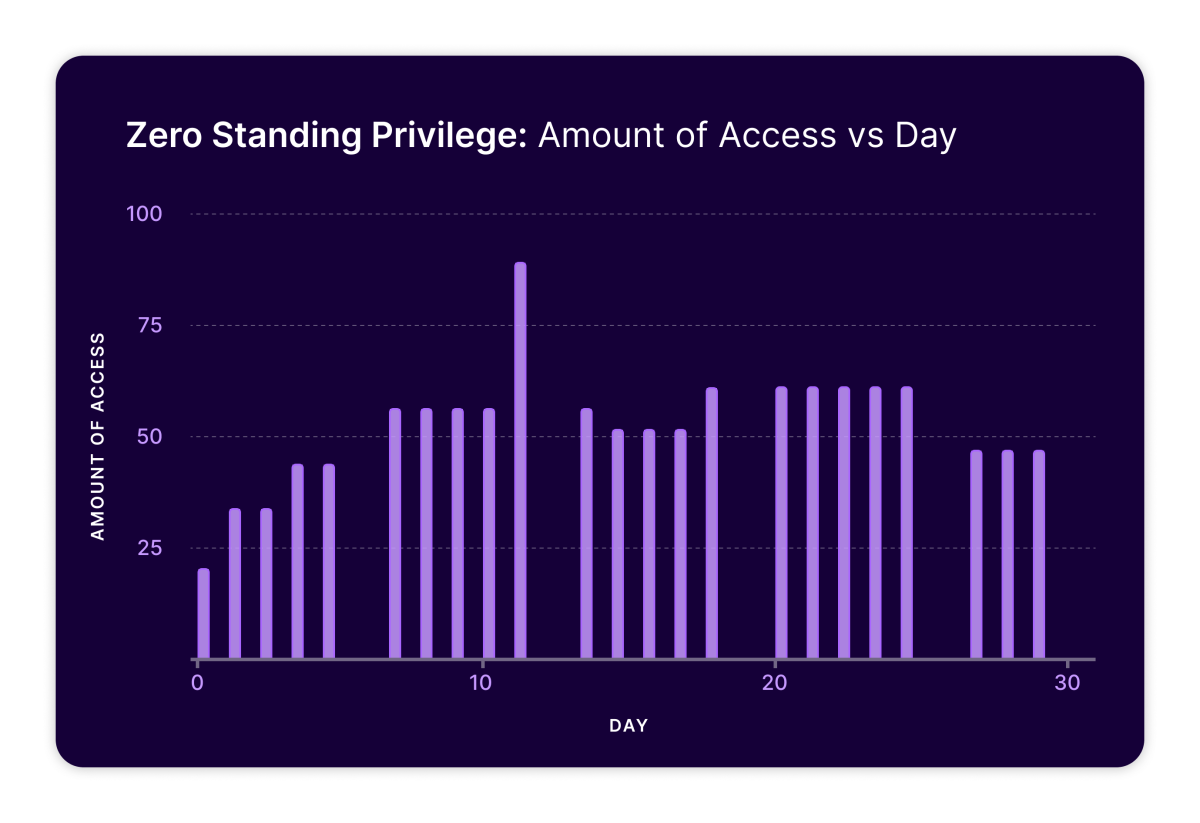

If we put this into practice, it would look something like this:

Zero Standing Privilege: Amount of Access Per Day

The same rules hold here – the area under the graph is access rights over time which represent what an adversary can use while living off the land.

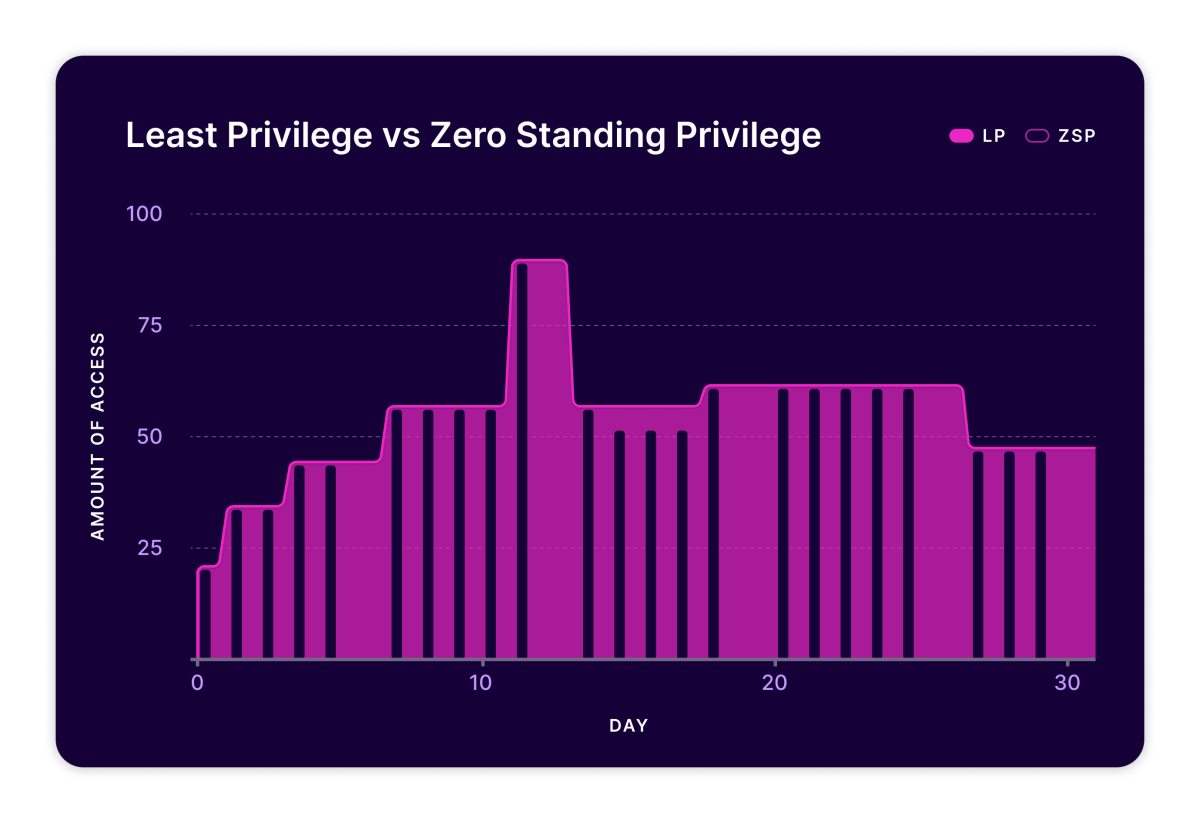

Least Privilege vs Zero Standing Privilege

Now let’s compare the two approaches LP as Destination and ZSP: the difference between the two graphs is the exploitable standing privilege. The first notable thing is the area under each line is vastly different. This is part due to weekends and off hours in which the individual doesn’t have a session and thus has no access rights to exploit. In a ZSP world, the area under the graph is zero when you don’t have a session or access token and this means there are no access rights to exploit or misuse… whereas in an LP world the access is still there in your user account.

Second, look at the big spike in access in both graphs; it represents a firefight incident in which the individual got extraordinary access to fix a production issue. Depending on the maturity of the IGA tools and processes, that extraordinary access might stick around a few days in an LP world, but not so in a ZSP world. And there’s a lot more nuance in these graphs which I’ll unpack in Part 2 of this post.

So now what?

First off, don’t stop doing what you are doing. IGA and access management teams need to keep doing the good work they are doing.

But, we need to start thinking about least privilege, not as a destination, but as the practice of continually removing standing access from user access. The destination is ZSP – that should be our North Star. To support this practice, we need to evaluate places in our architectures where access, based on documented auditable policy, can be granted at the time of use. Consider first where an adversary exploiting standing privilege can cause the most damage (e.g. network infrastructure, IaaS control plane, etc) and expand the scope from there.

I came to my IGA nihilism by realizing the challenges with entitlement catalogs. Others I have talked to come to their IGA nihilism through realizations about identity data and our relatively meager abilities to manage it. Regardless, there is a growing consensus that IGA has not lived up to its fullest potential. I think the simplest way to start rethinking our approaches with regards to IGA is to admit that least privilege as a destination is a lie, and start thinking about zero standing privilege as the place we all need to be moving towards.

[A special thank you to the SGNL team for making my crude graphs look waaaay better. – Ian]